Public Health

Ebola and Emerging Infectious Diseases: Lessons from Past Outbreaks

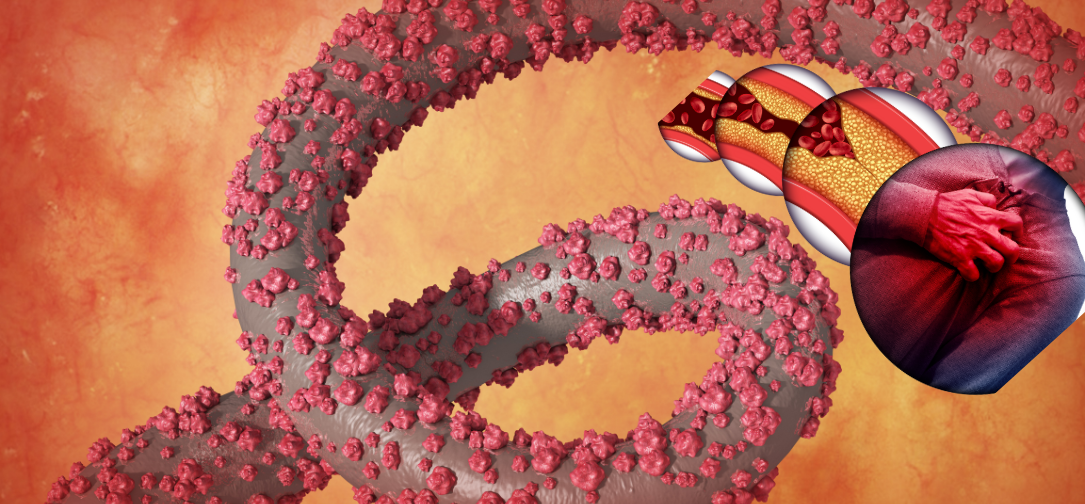

Emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) pose a significant threat to global health, economic stability, and social structures. These diseases, often caused by pathogens previously unknown or not recognized as significant threats, can lead to widespread outbreaks and pandemics. Among the many EIDs that have alarmed the world, the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) stands out for its high fatality rates, rapid spread, and profound social impact. The Ebola outbreaks, especially the West African epidemic from 2014 to 2016, serve as a grim reminder of the potential devastation caused by EIDs. Analyzing past Ebola outbreaks can provide valuable lessons for managing and preventing future outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases.

Understanding Ebola Virus Disease (EVD)

Ebola virus disease is a severe, often fatal illness caused by the Ebola virus, a member of the Filoviridae family. The disease was first identified in 1976 near the Ebola River in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Since then, it has led to sporadic outbreaks across Central and West Africa. The virus has five known species: Zaire, Sudan, Taï Forest, Bundibugyo, and Reston. The Zaire strain is the most virulent and has been responsible for the largest and deadliest outbreaks, including the 2014-2016 West African epidemic.

EVD is characterized by symptoms such as fever, severe headache, muscle pain, fatigue, diarrhea, vomiting, and, in severe cases, hemorrhaging. The virus is transmitted to humans from wild animals and spreads in the human population through direct contact with blood, secretions, or other bodily fluids of infected people or surfaces and materials (e.g., bedding, clothing) contaminated with these fluids. The case fatality rate for Ebola can range from 25% to 90%, depending on the virus strain and the quality of healthcare available.

Historical Context and Key Outbreaks of Ebola

1) 1976 Outbreaks in Sudan and Zaire (Democratic Republic of Congo):

The first recognized outbreaks of Ebola occurred almost simultaneously in Sudan and Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) in 1976. In Sudan, the outbreak began in a cotton factory in Nzara and resulted in 284 cases and 151 deaths, yielding a 53% case fatality rate. Around the same time, the Zaire outbreak, particularly around Yambuku, recorded 318 cases and 280 deaths, resulting in an 88% fatality rate. These outbreaks exposed the world to the lethality of the virus and the challenges of managing such a highly infectious disease in resource-limited settings.

2) 1995 Kikwit Outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo:

The 1995 outbreak in Kikwit, DRC, was another pivotal event in the history of Ebola. It caused 315 cases and 250 deaths, a fatality rate of about 81%. This outbreak highlighted the importance of infection control measures, as the virus spread extensively within hospitals due to the reuse of contaminated needles and lack of protective equipment. The Kikwit outbreak also marked one of the first instances where international organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) played significant roles in containing the virus.

3) 2000-2001 Uganda Outbreak:

Uganda experienced a significant outbreak in Gulu District in 2000-2001, resulting in 425 cases and 224 deaths (53% fatality rate). This outbreak underscored the need for community engagement and public health education, as containment efforts were initially hindered by mistrust of health workers and misunderstanding of the virus among the local population.

4) 2014-2016 West African Epidemic:

The 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak was the largest and most devastating in history, primarily affecting Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. This outbreak resulted in over 28,000 reported cases and more than 11,000 deaths, with a fatality rate of around 40%. Unlike previous outbreaks that were confined to remote, rural areas, this epidemic rapidly spread to densely populated urban centers and crossed national borders, complicating containment efforts. The scale and severity of this outbreak exposed significant weaknesses in global health preparedness and response mechanisms, leading to calls for reforms and better coordination among international health agencies.

5) 2018-2020 DRC Outbreak:

The 2018-2020 Ebola outbreak in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo was the second-largest on record, with 3,481 cases and 2,299 deaths. This outbreak posed unique challenges due to the ongoing conflict in the region, making it difficult for health workers to access affected communities and implement response measures. It highlighted the importance of security considerations in outbreak response and the need for integrating health and humanitarian efforts.

Lessons Learned from Past Ebola Outbreaks

1) Rapid Detection and Early Response:

One of the critical lessons from past Ebola outbreaks is the importance of rapid detection and early response. The longer it takes to identify and respond to an outbreak, the harder it becomes to control. The West African epidemic starkly illustrated this; delayed detection and a slow initial response allowed the virus to spread unchecked for several months, reaching urban centers and becoming a full-scale humanitarian crisis. Strengthening surveillance systems, especially in high-risk regions, and improving laboratory capacity for rapid diagnosis are essential measures for early detection and response.

2) Community Engagement and Trust-Building:

Community mistrust of health workers, coupled with cultural practices like traditional burials involving direct contact with the deceased, significantly contributed to the spread of Ebola during several outbreaks. In the 2014-2016 epidemic, rumors and misconceptions led to resistance against containment measures, attacks on healthcare workers, and the hiding of suspected cases. Building trust through effective community engagement, clear communication, and involving local leaders in response efforts are critical strategies. Health education campaigns that respect cultural practices while promoting safe behaviors can help bridge gaps between health workers and communities.

3) Infection Prevention and Control (IPC):

Infection prevention and control (IPC) measures are vital to preventing the spread of Ebola, particularly in healthcare settings. Many outbreaks, including the early ones in Zaire and Sudan, were exacerbated by the lack of IPC measures such as the reuse of contaminated needles and inadequate personal protective equipment (PPE). The West African outbreak saw a significant number of healthcare workers infected due to inadequate PPE and poor IPC practices. Strengthening IPC protocols, providing adequate PPE, and training healthcare workers in their use are fundamental to controlling Ebola and other EIDs.

4) Strong Health Systems and Infrastructure:

The 2014-2016 epidemic exposed the fragility of health systems in affected countries. Weak health infrastructures, limited healthcare workforce, poor access to essential medicines, and lack of surveillance capabilities contributed to the rapid spread of the virus and high mortality rates. Strengthening health systems to withstand the shock of outbreaks involves investing in healthcare infrastructure, training and retaining healthcare workers, ensuring supply chain resilience for medical supplies, and establishing robust disease surveillance systems.

5) Global Coordination and Support:

The global response to the West African epidemic was initially criticized for being slow and uncoordinated. However, once mobilized, the international community, including the WHO, CDC, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), and various governments, played a crucial role in containing the outbreak. The epidemic underscored the need for a well-coordinated global response to emerging infectious diseases, as outbreaks in one region can quickly become global threats. Mechanisms like the WHO’s Health Emergencies Program and the establishment of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) aim to facilitate more timely and coordinated responses to future outbreaks.

6) Research and Development of Medical Countermeasures:

The 2014-2016 outbreak catalyzed research and development for Ebola vaccines and treatments. The rapid development of the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine, which proved highly effective during the 2018-2020 DRC outbreak, demonstrated the value of investment in medical research and public-private partnerships. Continued investment in research for vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostic tools is critical for preparedness against EIDs. The accelerated development of these tools also benefited from adaptive trial designs and regulatory flexibility, offering a model for future EID research.

7) Integrated Approach to One Health:

Ebola, like many other EIDs, is a zoonotic disease, meaning it is transmitted from animals to humans. Understanding the dynamics of zoonotic transmission is crucial for preventing outbreaks. The One Health approach, which integrates human, animal, and environmental health, is essential in addressing the interconnectedness of these factors. Monitoring wildlife, controlling illegal bushmeat trade, and managing human-wildlife interactions are vital for preventing spillover events.

8) Addressing Social Determinants of Health:

The West African Ebola epidemic highlighted the role of social determinants, such as poverty, lack of education, inadequate water and sanitation, and political instability, in driving the spread of infectious diseases. Addressing these underlying determinants is crucial for effective outbreak prevention and response. Building resilient communities through education, economic empowerment, and improved living conditions can reduce the vulnerability to EIDs.

9) Ethical Considerations in Outbreak Response:

Ebola outbreaks have raised several ethical concerns, including the allocation of limited resources, the use of experimental treatments, and the rights of affected individuals and communities. Balancing public health priorities with individual rights requires careful consideration and transparency. Engaging with communities, ensuring informed consent, and maintaining trust are vital components of ethical outbreak response.

10) Preparedness and Simulation Exercises:

Preparedness is key to mitigating the impact of emerging infectious diseases. Conducting regular simulation exercises, developing national and international emergency response plans, and maintaining stockpiles of essential medical supplies can

enhance readiness for future outbreaks. The Ebola outbreaks have shown that preparedness is not just about having a plan but also about testing and refining it regularly.

Emerging Infectious Diseases Beyond Ebola

Ebola is not an isolated case; it represents a broader category of EIDs that have emerged in recent decades, including Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), Zika virus, Nipah virus, and the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). These diseases, often originating in animals and jumping to humans, have demonstrated how interconnected our world is and how quickly a local outbreak can become a global threat. The lessons from Ebola are applicable across the spectrum of EIDs, reinforcing the need for a comprehensive and coordinated approach to global health security.

Conclusion

Ebola and other emerging infectious diseases will continue to challenge global health systems, economies, and societies. The lessons learned from past Ebola outbreaks provide a roadmap for improving preparedness, response, and resilience to future EIDs. Strengthening health systems, enhancing surveillance and early detection, fostering community engagement, investing in research and development, and promoting global coordination are essential elements of an effective strategy to combat emerging infectious diseases. The future of global health security depends on our ability to learn from past experiences and build a more robust, equitable, and resilient global health architecture.

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoS&P 500 Soars in Best May in Decades Amid Tariff Relief and Nvidia’s Surge

-

Healthcare6 days ago

Healthcare6 days agoAttention Economy Arms Race: Reclaim Your Focus in a World Designed to Distract You

-

Immigration5 days ago

Immigration5 days agoTrump’s Immigration Crackdown: Legal Battles and Policy Shifts

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoUS Stock Market Soars in May Amidst Tariff Tensions and Inflation Worries

-

Government5 days ago

Government5 days agoTrump Administration’s Government Reshaping Efforts Face Criticism and Legal Battles

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoTrump’s Tariffs: A Global Economic Reckoning

-

Foreign Policy2 days ago

Foreign Policy2 days agoInside Schedule F: Will Trump’s Federal Workforce Shake-Up Undermine Democracy?

-

Press Release2 days ago

Press Release2 days agoIn2space Launches Campaign to Make Space Travel Accessible for All