Innovations

Cracking Enigma: How the First Computer Program on September 1, 1939, Ignited the Modern Computing Revolution

On September 1, 1939, as the world teetered on the brink of global conflict, a pivotal event in the history of computing quietly unfolded in the English countryside. At Bletchley Park, a secretive estate that would become synonymous with cryptography and wartime intelligence, the first operational use of a machine known as the Bombe marked the beginning of a new era. This electromechanical device, designed to decipher the seemingly impenetrable Enigma-encrypted signals of Nazi Germany, not only played a critical role in the Allied war effort but also laid the foundation for the modern computer revolution. This article explores the origins, development, and legacy of the Bombe, providing a detailed account of how it catalyzed the birth of modern computing.

The Context: A World at War and the Need for Intelligence

As Europe inched closer to war in the late 1930s, the need for reliable intelligence became increasingly apparent. The German military, having learned from the mistakes of World War I, understood the importance of secure communication. To this end, they adopted the Enigma machine, an encryption device that was believed to be unbreakable. The Enigma machine used a complex system of rotors and electrical circuits to encode messages, ensuring that even if the signal was intercepted, it would be virtually impossible to decipher without knowing the precise settings of the machine.

The Enigma’s encryption process was based on a series of rotors, each of which could be set to one of 26 positions, corresponding to the letters of the alphabet. As a message was typed into the machine, the rotors would rotate, changing the electrical pathways and producing an encoded version of the original message. The settings of the rotors were changed daily according to secret key lists, making it incredibly difficult for anyone without access to these lists to break the code.

For the Allies, breaking the Enigma code became a matter of utmost importance. The ability to read German communications would provide invaluable insights into enemy strategies, troop movements, and logistical plans, potentially turning the tide of the war. However, the complexity of the Enigma machine posed a formidable challenge. Early efforts to break the code relied on human cryptanalysts, who worked tirelessly to decipher intercepted messages. While they had some successes, it quickly became clear that a more systematic, mechanical approach was needed to keep up with the sheer volume of encrypted communications.

The Genesis of the Bombe: From Concept to Reality

The Bombe’s origins can be traced back to the work of Polish cryptanalysts in the early 1930s. As tensions in Europe mounted, the Polish Cipher Bureau began an intensive effort to crack the Enigma code. They achieved notable success by exploiting weaknesses in the German encryption procedures, but their methods were labor-intensive and required access to key settings that were not always available. Recognizing the limitations of their approach, the Poles developed a device known as the “Bomba,” a precursor to the Bombe, which automated some of the process of testing possible Enigma settings.

When war became imminent, the Polish cryptographers shared their knowledge and techniques with their British counterparts, providing them with crucial insights that would form the basis of the Bombe’s development. Among those who took up the challenge of building a more advanced version of the Bomba was Alan Turing, a brilliant mathematician whose work would become legendary in the field of computer science.

Turing, along with fellow cryptanalyst Gordon Welchman, set to work on designing a machine that could automate the process of testing Enigma settings on a much larger scale. Their design, which would come to be known as the Bombe, was based on the principle of “cribs”—educated guesses about certain parts of the message. By comparing the encoded message with these known cribs, the Bombe could rapidly eliminate possible rotor settings, narrowing down the possibilities until the correct settings were found.

The Bombe was a complex electromechanical device, consisting of rotating drums, electrical circuits, and a system of relays that simulated the operation of the Enigma machine. Each Bombe was capable of testing thousands of rotor settings per second, a feat that would have been impossible to achieve by hand. The machines were built by the British Tabulating Machine Company, under the direction of Harold Keen, with the first operational Bombe being delivered to Bletchley Park in March 1940.

Bletchley Park: The Nerve Center of Codebreaking

Bletchley Park, a Victorian mansion located about 50 miles northwest of London, became the epicenter of British codebreaking efforts during World War II. The estate was chosen for its secluded location and proximity to key transport links, making it an ideal site for a secret intelligence operation. As war loomed, the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) was relocated to Bletchley, and the estate was quickly transformed into a hive of cryptographic activity.

At Bletchley Park, a diverse team of mathematicians, linguists, engineers, and even chess champions worked together in secrecy to decipher enemy communications. The team included some of the brightest minds of the era, such as Alan Turing, Gordon Welchman, and Hugh Alexander. Their work was highly compartmentalized, with different groups focusing on different aspects of the codebreaking process. This division of labor was essential to maintaining the secrecy of the operation, as few individuals had a complete picture of what was happening at Bletchley.

The Bombe played a central role in the work of Bletchley Park, particularly in the section known as Hut 8, where Turing and his team focused on breaking Naval Enigma, the version of the Enigma cipher used by the German Navy. Naval Enigma was considered the most difficult to crack due to the higher level of encryption used and the critical importance of secure communications for U-boat operations in the Atlantic. The ability to read these communications was vital for the Allies, as it allowed them to anticipate and counter the devastating U-boat attacks on Allied shipping.

The First Operational Use: September 1, 1939

September 1, 1939, is a date that marks the official start of World War II, with Germany’s invasion of Poland triggering a chain of events that would engulf the world in conflict. On the same day, the Bombe was put into operational use at Bletchley Park, marking the beginning of a new chapter in the history of computing and cryptography.

The first Bombe, known as “Victory,” was a prototype that had been hastily assembled in response to the urgent need for a more efficient codebreaking tool. Despite its makeshift nature, the Victory Bombe proved its worth almost immediately. On that day, it successfully deciphered a series of intercepted German messages, providing the British military with valuable intelligence that would help shape their early war strategy.

The success of the Victory Bombe led to the rapid production of more machines, with each successive model being more reliable and capable than the last. By the end of the war, there were over 200 Bombes in operation at Bletchley Park and other secret locations around the United Kingdom. These machines ran day and night, manned by teams of operators who worked in shifts to ensure that no critical message went undeciphered.

The information gleaned from the Bombe’s efforts was fed into a larger intelligence network, code-named “Ultra,” which disseminated the decrypted messages to military commanders and government officials. The Ultra intelligence was a closely guarded secret, known only to a select few, and it played a crucial role in many of the Allies’ most significant victories, including the Battle of the Atlantic, the North African campaign, and the D-Day invasion.

The Bombe’s Technical Design and Operation

The Bombe was an engineering marvel of its time, combining the principles of mechanical computation with the nascent field of electronic logic. The machine’s design was based on the concept of combinatorial analysis, a mathematical technique that involves testing multiple combinations of variables to find a solution to a problem.

At its core, the Bombe consisted of a series of rotating drums, each representing one of the Enigma machine’s rotors. These drums were wired together in a way that simulated the electrical pathways of the Enigma machine, allowing the Bombe to test different rotor settings against a given ciphertext. The drums rotated in synchronization, rapidly cycling through possible settings while the machine’s electrical circuits checked for logical consistency with the known cribs.

When the Bombe found a match, it would halt, and a set of indicator lights would show the possible rotor settings that could have produced the intercepted message. These settings were then passed on to human cryptanalysts, who would use them to decode the full message using a replica Enigma machine.

The Bombe’s operation was not entirely automated; it required skilled operators to set up the machine, monitor its progress, and interpret the results. These operators, often women recruited from universities and technical colleges, played a crucial role in the success of the Bombe. Their work was demanding and required a high level of concentration, as a single mistake could lead to a critical message being missed.

Despite its complexity, the Bombe was designed to be as user-friendly as possible, given the technology of the time. The machine’s interface was relatively simple, with dials and switches that allowed operators to input the crib and adjust the machine’s settings. The results were displayed using indicator lights, which were easy to read and interpret even under the pressure of wartime conditions.

The Bombe’s Role in Shaping Modern Computing

The Bombe was more than just a codebreaking tool; it was a pioneering step in the development of modern computing. The principles that underpinned the Bombe’s operation—automation, logical analysis, and the use of electrical circuits to perform complex calculations—would later be applied to the design of early digital computers.

Alan Turing, who played a central role in the Bombe’s development, is often regarded as the father of computer science. His work on the Bombe provided him with valuable insights into the nature of computation and the potential for machines to perform tasks that had previously been the domain of human intellect. These ideas would later be formalized in Turing’s concept of the “universal machine,” a theoretical construct that laid the groundwork for the modern computer.

The Bombe also demonstrated the power of automation in solving complex problems. Before the Bombe, codebreaking was a largely manual process, relying on human intuition and trial-and-error to decipher messages. The Bombe, by contrast, could perform thousands of calculations per second, far surpassing the capabilities of any human cryptanalyst. This shift from manual to automated problem-solving was a key moment in the history of computing, highlighting the potential for machines to augment and enhance human capabilities.

In addition to its technical innovations, the Bombe also had a profound impact on the organization and management of information. The sheer volume of data generated by the Bombe’s operations required new methods of data storage, retrieval, and analysis, leading to the development of early forms of data management systems. These systems, though rudimentary by today’s standards, were the precursors to the databases and information management technologies that are now integral to modern computing.

The Legacy of the Bombe and Bletchley Park

The Bombe’s legacy is most evident in the post-war era, as the techniques and technologies developed at Bletchley Park laid the foundation for the computer revolution of the 20th century. Many of the individuals who worked on the Bombe went on to make significant contributions to the field of computing, bringing their wartime experiences to bear on the development of new technologies.

Alan Turing, in particular, continued to explore the possibilities of machine computation after the war, leading to his work on the ACE (Automatic Computing Engine) and his theoretical explorations of artificial intelligence. Turing’s ideas, once considered radical, have since become central to the field of computer science, influencing generations of researchers and developers.

The secrecy surrounding the Bombe and the work of Bletchley Park meant that the full extent of their contributions was not widely known until decades after the war. It was not until the 1970s that the story of Bletchley Park and the Bombe began to emerge, leading to a renewed interest in the history of computing and cryptography.

Today, Bletchley Park is a museum and heritage site, dedicated to preserving the memory of the codebreakers and their work. The Bombe has been recognized as a key milestone in the history of computing, and several working replicas have been built to demonstrate its operation to the public. These replicas serve as a testament to the ingenuity and determination of the individuals who built and operated the Bombe, as well as a reminder of the machine’s enduring significance.

Conclusion: The Bombe as a Catalyst for Change

The Bombe, first used operationally on September 1, 1939, was a groundbreaking innovation that played a pivotal role in the Allied victory during World War II. Its ability to decipher the complex Enigma code provided the Allies with crucial intelligence, helping to shape the course of the war and save countless lives.

However, the Bombe’s significance extends far beyond its wartime role. It was a key step in the development of modern computing, introducing concepts and techniques that would later be refined and expanded upon in the digital age. The Bombe demonstrated the power of automation and logical analysis in solving complex problems, paving the way for the creation of the first digital computers and the subsequent explosion of technological innovation.

The legacy of the Bombe is reflected in the world we live in today, where computers and automated systems are integral to nearly every aspect of our lives. From the smartphones in our pockets to the servers that power the internet, the principles that guided the development of the Bombe continue to influence the design and operation of modern technology.

As we reflect on the history of the Bombe and its impact, it is important to recognize the individuals who made this remarkable achievement possible. The story of the Bombe is a story of collaboration, innovation, and perseverance in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges. It is a story that continues to inspire and inform the ongoing quest to push the boundaries of what is possible with technology.

-

Press Release6 days ago

Press Release6 days agoNura Labs Files Revolutionary Patent: AI-Powered Wallet Solves the $180 Billion Crypto Staking Complexity Crisis

-

Press Release4 days ago

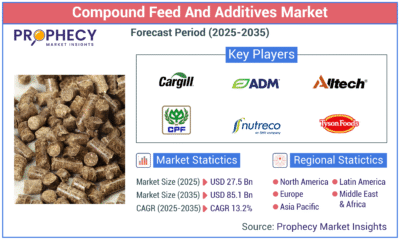

Press Release4 days agoGlobal Compound Feeds and Additives Industry Report: Market Expansion and Competitive Insights to 2035

-

Technology4 days ago

Technology4 days agoWhat to Know Before Switching Cell Phone Network Services in 2025

-

Press Release2 days ago

Press Release2 days agoCrypto WINNAZ Launches First On-Chain Yield Engine for Meme Coins, Enabling 20x–300x Returns