Public Health

Understanding Epidemiology and Its Application in Public Health

Epidemiology is a discipline in public health that examines the distribution, determinants, and deterrents of health-related events in populations. It provides the scientific foundation for public health practice. Through the lens of epidemiology, we can understand the patterns of diseases, identify risk factors, and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions. This comprehensive understanding allows public health professionals to design and implement strategies that prevent disease, prolong life, and promote health on a population level.

This article provides an in-depth exploration of epidemiology, its core principles and methodologies, and its critical role in shaping public health initiatives. We will also examine epidemiology’s practical applications in addressing current public health challenges, from infectious disease outbreaks to chronic disease prevention and health policy formulation.

1) The Foundations of Epidemiology

Epidemiology is derived from the Greek words “epi,” meaning upon; “demos,” meaning people; and “logos,” meaning study. Hence, epidemiology is essentially the study of what befalls a population. This field is rooted in the basic concepts of disease distribution and the determinants of health-related events.

1.1 The Core Concepts

Disease Distribution: Epidemiology investigates how disease and health conditions are distributed in populations. This involves analyzing patterns by age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, geographical location, and time. Understanding these patterns helps identify vulnerable populations and the burden of disease.

Determinants: Determinants are factors that influence disease and health events. These can be biological, environmental, social, or behavioral. Epidemiologists study these determinants to understand what causes or contributes to health outcomes in a population.

Outcomes: Epidemiology studies outcomes related to various health-related states or events, such as infections, chronic diseases, injuries, and behaviors like smoking or physical activity. The focus is not just on diseases but also on other health conditions affecting quality of life.

Populations: Unlike clinical medicine, which focuses on individual patients, epidemiology focuses on populations. The goal is to understand health trends at a community, regional, national, or global level, informing public health actions.

1.2 Historical Evolution of Epidemiology

Epidemiology has evolved significantly over the centuries, with its roots tracing back to ancient times when early civilizations attempted to understand the causes of diseases. However, the field truly began to take shape during the 19th century.

Early Observations: Hippocrates, often called the “Father of Medicine,” was among the first to suggest that environmental and behavioral factors might influence health. He proposed that disease was not solely due to supernatural causes but could be linked to the environment and lifestyle.

The Birth of Modern Epidemiology: The modern era of epidemiology began in the 19th century with John Snow’s investigation of a cholera outbreak in London. By mapping cholera cases, Snow identified a contaminated water pump as the source of the epidemic, demonstrating the power of systematic observation and data analysis in understanding disease patterns. This was a pivotal moment that established epidemiology as a scientific discipline.

The Germ Theory: Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch developed the germ theory, which further advanced epidemiology by providing a biological explanation for infectious diseases. This theory posited that microorganisms cause many diseases and shifted the epidemiology focus to identifying and controlling contagious agents.

Epidemiology in the 20th Century: The 20th century saw significant advancements in epidemiological methods and the expansion of the field to include chronic diseases, injuries, and health behaviors. The Framingham Heart Study, initiated in 1948, is a landmark example of how long-term epidemiological studies can identify risk factors for chronic diseases such as heart disease.

2) Epidemiological Methods and Study Designs

Epidemiology relies on various study designs and methods to investigate health-related events. These methods are critical for identifying associations between risk factors and outcomes, testing hypotheses, and evaluating interventions.

2.1 Descriptive Epidemiology

Descriptive epidemiology describes the distribution of disease and health outcomes in populations. It answers the “who,” “what,” “when,” and “where” of health events.

Case Reports and Case Series: These are descriptive studies that provide detailed information about individual cases (case reports) or groups of cases (case series). They are often the first indication of a new disease or health trend.

Cross-Sectional Studies: These studies assess the health status of a population at a single point in time. Cross-sectional studies help determine the prevalence of diseases and identify potential associations between risk factors and outcomes.

Ecological Studies: Ecological studies analyze data at the population or group level rather than the individual level. These studies can reveal associations between exposure and disease across different populations, but they are limited by the ecological fallacy, where group-level associations may not hold at the individual level.

2.2 Analytical Epidemiology

Analytical epidemiology seeks to understand the causes and determinants of health outcomes. It answers the “how” and “why” questions by testing specific hypotheses.

Cohort Studies: Cohort studies follow a group of individuals over time to assess how exposure to certain risk factors affects disease development. Cohort studies can be prospective (looking forward in time) or retrospective (looking back at past exposures). The Framingham Heart Study is a classic example of a cohort study.

Case-Control Studies: Case-control studies compare individuals with a disease or health outcome (cases) to those without the disease (controls) to identify factors that may have contributed to the outcome. These studies are particularly useful for studying rare diseases.

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs): RCTs are considered the gold standard for testing the efficacy of interventions. In an RCT, participants are randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group, allowing researchers to determine whether the intervention significantly impacts the outcome.

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: These methods involve synthesizing data from multiple studies to understand a particular health issue comprehensively. Systematic reviews follow a rigorous protocol to identify and evaluate studies, while meta-analyses use statistical techniques to combine data and generate pooled effect estimates.

3) Key Applications of Epidemiology in Public Health

Epidemiology is not just an academic discipline; it is a practical tool that public health professionals use to improve population health. The following sections explore some of the critical applications of epidemiology in public health.

3.1 Disease Surveillance and Outbreak Investigation

One of the most critical applications of epidemiology is in disease surveillance and outbreak investigation. Surveillance systems are designed to continuously monitor the occurrence of diseases in populations, allowing for the early detection of outbreaks and the implementation of control measures.

Surveillance Systems: Epidemiologists develop and maintain surveillance systems to track the incidence and prevalence of diseases. These systems can be passive (relying on healthcare providers to report cases) or active (where public health officials actively seek out cases). Examples include the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS).

Outbreak Investigation: When a disease outbreak is detected, epidemiologists play a crucial role in investigating the outbreak to identify the source, mode of transmission, and affected populations. An outbreak investigation typically involves verifying the outbreak, defining and identifying cases, describing the outbreak by time, place, and person, developing hypotheses, testing hypotheses, and implementing control measures.

Case Study—The Ebola Outbreak: The Ebola outbreak in West Africa from 2014 to 2016 highlighted the importance of epidemiology in outbreak response. Epidemiologists were instrumental in tracking the spread of the virus, identifying transmission patterns, and informing public health interventions that ultimately helped control the outbreak.

3.2 Chronic Disease Epidemiology

While epidemiology has traditionally focused on infectious diseases, the rise of chronic diseases, such as heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and obesity, has shifted some of the focus toward understanding the determinants of these conditions.

Risk Factor Identification: Epidemiologists study the risk factors associated with chronic diseases, such as smoking, physical inactivity, poor diet, and genetic predisposition. By identifying these risk factors, public health professionals can develop targeted interventions to reduce the burden of chronic diseases.

Prevention Programs: Epidemiology informs the design and evaluation of chronic disease prevention programs. For example, the success of smoking cessation programs and policies to reduce tobacco use has been largely driven by epidemiological evidence linking smoking to lung cancer and other diseases.

Case Study – The Framingham Heart Study: The Framingham Heart Study, initiated in 1948, is one of the most famous epidemiological studies of chronic disease. This longitudinal study identified major cardiovascular risk factors, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity, and has dramatically influenced public health strategies for heart disease prevention.

3.3 Infectious Disease Control and Prevention

Infectious diseases remain a major public health challenge, particularly with the emergence of new pathogens and the re-emergence of diseases once thought to be under control. Epidemiology is central to controlling and preventing infectious diseases.

Vaccination Programs: Epidemiology is critical in designing, implementing, and evaluating vaccination programs. By understanding the epidemiology of infectious diseases, public health officials can determine which populations should be targeted for vaccination, how vaccines should be distributed, and the impact of vaccination programs on disease incidence.

Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR): Epidemiologists study antimicrobial resistance patterns, a growing global health threat. By identifying trends in resistance, epidemiology helps guide the

appropriate use of antibiotics and developing strategies to mitigate the spread of resistant organisms.

Global Health Initiatives: Epidemiology is crucial in global health initiatives to control infectious diseases. For example, the worldwide effort to eradicate polio relies heavily on epidemiological data to target vaccination campaigns and monitor progress.

Case Study – The COVID-19 Pandemic: The COVID-19 pandemic is a recent example of how epidemiology is essential for managing infectious disease outbreaks. From tracking the spread of the virus to identifying risk factors for severe disease, epidemiologists have been at the forefront of the global response, guiding public health interventions such as social distancing, mask-wearing, and vaccination.

3.4 Environmental and Occupational Epidemiology

Environmental and occupational epidemiology focuses on understanding how environmental exposures, such as air pollution, chemicals, and workplace hazards, affect health.

Exposure Assessment: Epidemiologists assess exposures to environmental and occupational hazards and study their associations with health outcomes. This can involve measuring environmental pollutants, estimating exposure levels, and linking them to disease occurrence.

Policy Development: Epidemiological evidence is often used to inform environmental and occupational health policies. For example, research on the health effects of air pollution has led to regulations that limit emissions from industrial sources and vehicles.

Case Study—The Clean Air Act: The U.S. Clean Air Act regulates air pollution and is grounded in epidemiological research demonstrating the harmful effects of pollutants like particulate matter and ozone on human health. Implementing this act has led to significant improvements in air quality and reductions in respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

3.5 Health Policy and Public Health Decision-Making

Epidemiology provides the evidence base for health policy and public health decision-making. By identifying health trends, risk factors, and the effectiveness of interventions, epidemiology helps policymakers make informed decisions.

Health Impact Assessments (HIAs): HIAs are a tool used to evaluate the potential health effects of a policy, program, or project before it is implemented. Epidemiologists conduct HIAs to provide evidence-based recommendations that protect and promote public health.

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Epidemiologists often conduct cost-effectiveness analyses to determine the best use of limited public health resources. These analyses compare different interventions’ costs and health outcomes, helping policymakers prioritize actions that provide the greatest health benefits at the lowest price.

Case Study – Tobacco Control Policies: Epidemiological research has been instrumental in shaping tobacco control policies worldwide. Studies showing the link between smoking and diseases like lung cancer and heart disease have led to the implementation of policies such as smoking bans, tobacco taxes, and public health campaigns, which have significantly reduced smoking rates and related diseases.

4) The Future of Epidemiology in Public Health

Epidemiology will also continue to evolve as a field of public health. Emerging trends and challenges will likely shape the field’s future and its application in public health.

4.1 Big Data and Epidemiology

The advent of big data has opened new opportunities for epidemiology. By analyzing vast amounts of data from various sources, such as electronic health records (EHRs), social media, and wearable devices, epidemiologists can gain deeper insights into health patterns and determinants.

Real-Time Surveillance: Big data allows for real-time disease surveillance, enabling quicker identification of outbreaks and more timely public health responses.

Personalized Public Health: The integration of big data with genomic information and other personal health data is paving the way for personalized public health, where interventions can be tailored to individual risk profiles.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations: While big data offers significant potential, it also presents challenges, such as ensuring data privacy, addressing biases in data collection, and interpreting complex datasets.

4.2 Globalization and Emerging Infectious Diseases

Globalization has increased the potential for the rapid spread of infectious diseases, making global health a critical focus for epidemiologists.

Pandemic Preparedness: The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of global epidemiological surveillance and preparedness. Strengthening international cooperation and data sharing will be essential for managing future pandemics.

One Health Approach: The One Health approach, which recognizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health, is gaining traction in epidemiology. This approach is particularly relevant for emerging zoonotic diseases, which are transmitted from animals to humans.

4.3 Climate Change and Health

Climate change is expected to have profound effects on public health, presenting new challenges for epidemiology.

Changing Disease Patterns: Climate change is likely to alter the distribution of diseases, particularly vector-borne diseases like malaria and dengue fever. Epidemiologists will need to monitor these changes and develop strategies to mitigate their impact.

Environmental Health: The health effects of climate-related events, such as heatwaves, floods, and wildfires, will require a strong epidemiological response to protect vulnerable populations and inform public health interventions.

4.4 Equity and Social Determinants of Health

Addressing health disparities and the social determinants of health will remain a priority for epidemiology in the future.

Health Equity Research: Epidemiologists are increasingly focused on understanding and addressing the root causes of health disparities. This includes studying how social, economic, and environmental factors contribute to health inequities and developing interventions that promote health equity.

Community-Engaged Epidemiology: Engaging communities in epidemiological research and public health initiatives is essential for ensuring that interventions are culturally relevant and effective. This approach helps build trust and ensures that research findings translate into meaningful health improvements.

Conclusion

Epidemiology is a vital discipline that underpins public health efforts to understand and improve the health of populations. From its historical roots in the study of infectious diseases to its modern applications in chronic disease prevention, environmental health, and global health, epidemiology continues to evolve and adapt to new challenges.

The future of epidemiology will be shaped by advancements in technology, the emergence of new health threats, and the ongoing pursuit of health equity. As we move forward, the principles and methods of epidemiology will remain essential tools for public health professionals, guiding their efforts to protect and promote the health of all people.

By embracing the power of epidemiology, public health can continue to make significant strides in preventing disease, prolonging life, and enhancing the quality of life for populations around the world.

-

Press Release6 days ago

Press Release6 days agoNura Labs Files Revolutionary Patent: AI-Powered Wallet Solves the $180 Billion Crypto Staking Complexity Crisis

-

Press Release4 days ago

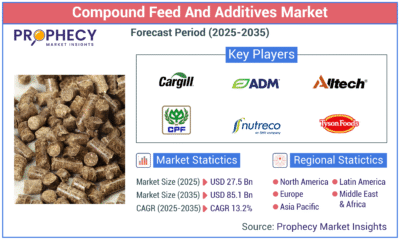

Press Release4 days agoGlobal Compound Feeds and Additives Industry Report: Market Expansion and Competitive Insights to 2035

-

Technology3 days ago

Technology3 days agoWhat to Know Before Switching Cell Phone Network Services in 2025

-

Press Release2 days ago

Press Release2 days agoCrypto WINNAZ Launches First On-Chain Yield Engine for Meme Coins, Enabling 20x–300x Returns